Historian Amy Bertsch recounted the life of Hannah Nokes, likely a transgender person in 1930s Northern Virginia.

This is the second of a two-part series reporting on the November 2 Fairfax County History Commission’s conference. Part 1 was in the Nov. 7 Connection newspapers.

The theme, “The Power of Place,” permeated the Fairfax County History Commission’s 20th annual conference on Nov. 2, including the power of places long gone.

Keynoter and filmmaker Ron Maxwell challenged the 130 attendees to discard all preconceptions when studying history. U.S. Rep. Gerry Connolly urged the audience to “tell our true history,” warts and all.

Two speakers spotlighted two minority communities that no longer exist, but the power of those places persists in memories and legacies, they said.

Segregated Military Housing

Judge Rouhulamin Quander, a retired Washington, D.C. administrative law judge, traces his family back 11 generations to the 1670s, one of the oldest documented African-American families in the United States. Encyclopedia Virginia reports that Egya Amkwandoh was kidnapped in Ghana and forcibly brought to America enslaved. When asked his name, he answered “Amkwandoh,” which was misinterpreted as, “I am Quando.” Eventually, the Quandos or Quanders acquired land in the Mount Vernon area and Maryland.

Quander described Youngs Village, a community inside today’s Fort Belvoir that the U.S. Army built as segregated housing for African- American soldiers and their families in the 1940s, and named for African American Officer Colonel Charles Young. At first, the children had to travel five miles to school in Gum Springs, but in 1946, the Army built the Belvoir Colored School, Quander said.

In 1948, President Harry Truman ordered that the military be desegregated. In the 1950s, the families in Youngs Village were forced to move and the homes demolished. Army officials eventually named its seven streets for African American soldiers killed in World War II. The Army also renamed Robert E. Lee Road to EO 9981, for Truman’s executive order abolishing segregation.

Noting that George Washington enslaved some Quanders, Judge Quander concluded, “This is not African American history. It’s history from an African-American perspective.”

Merrifield’s Past Communities

African-American ethnographer Marion Dobbins opened by declaring, “I do not have a home to go back to.” One of her ancestors in 1874 bought land in Mills Crossroads, today the Merrifield area, and helped establish a community called The Pines, one of three African-American communities in the area. Dobbins fondly recalled her grandmother’s accounts of this close-knit community.

The early residents were truck farmers who grew produce and sold it in Washington, D.C. In 1894, families built the First Baptist Church of Merrifield and in 1898, a “colored school” which stood until 1964, still without electricity or indoor plumbing.

In 1964, the Fairfax County School Board sent residents of The Pines a letter indicating that the county would build a school on their land, giving them 60 days to move and threatening to use eminent domain if necessary. The county offered $16,000 to each property owner, people who were mostly mortgage free. Dobbins’s grandmother moved to a neighboring town called Williamstown, an African American community on today’s Gallows Road, roughly what is now Fairfax Hospital. Suddenly, at age 64, she was saddled with a mortgage. The Pentagon’s construction displaced African Americans who moved to Williamstown, Dobbins said.

“Fairfax County never built the school,” said Dobbins. “It’s now a soccer field and community gardens.” A county marker recognizes the displaced community and cemetery where church members are buried.

Dobbins recalled that growing up in segregated times, “We could not go to the Merrifield Drive-in.” When buying new shoes, her mother had to draw her foot on a piece of paper to match the shoe size because she was not allowed to put on the shoes or try on clothes. Fairfax County “has come a long way,” Dobbins said. “We now are embracing our history. Black history is American history. You cannot have history without all of it.”

Dobbins fears that the country is “returning to the lost cause scenario,” an ideology that tried to justify the Civil War as a just cause and reframed slavery as states’ rights. Dobbins satirized, “When slaves loved to be slaves and life was nice.”

“We were a family and we had a home. We don’t have a hometown now,” she lamented.

Gender Variant in the 1930s

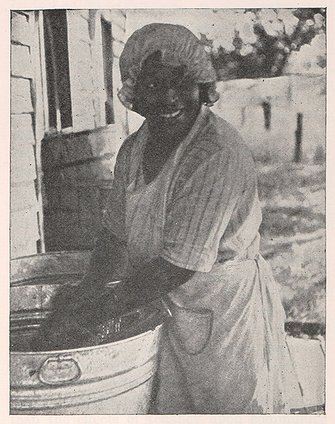

Historian Amy Bertsch told the story of someone that records call both Hammond Nokes and Hannah Nokes, a person assigned as male at birth and probably gender variant. She worked for the McMillan family in Herndon, did laundry and later ran a boarding house. When called as the prosecution’s witness in a 1932 murder trial, Hannah wore a wig, hat, dress and necklace. Reporters described her as a “boy/girl, a fairy, a lady man.” During the trial, her nephew identified her as his aunt.

Pictured in a 1936 magazine promoting rural electrification, Hannah was “known for her industry and good nature … and is regarded with affection and respect by her neighbors,” the article stated. When Hannah was hospitalized, nurses discovered she was biologically male. She wore a blue dress in her coffin in 1872. One death notice identified her as Miss Hammond Nokes and another as Hammond (Hanna) Nokes.

History is not simple or straightforward, attendees heard. Dr. Ted McCord, retired George Mason University history professor, said, “Local history conferences help us link residents to their surrounding communities, giving them greater understanding and appreciation for those who have gone before them. Conferences also can inspire local people to pursue their family histories and their contributions to their neighborhoods.”

The History Commission gave several awards including the Lifetime Achievement Award to Mount Vernonite Glenn Fatzinger.